If you ever have the opportunity to visit the Whydah Museum in West Yarmouth, MA, I strongly recommend that you take a look. I was there last week, and although the history of the Whydah ship, a slave ship captured and turned into a pirate ship, was interesting, what I found truly fascinating was the way that the Whydah’s artifacts were found and revealed.

The Whydah met its untimely demise when a storm blew up in a bad nor’easter in April of 1717. After a struggle to keep her afloat, the Whydah hit a sandbar off the coast of Wellfleet, Cape Cod and sank. Although many knew of the Whydah‘s sinking, it wasn’t until 1985 that the ship’s bell was discovered by Barry Clifford. Artifacts of the Whydah have been slowly being brought to light ever since.

When metals are left for some time underwater, as would have happened in a shipwreck like the Whydah, they begin to disintegrate and combine with the ocean water’s salt. In time, rock, clay, sand, as well as other artifacts combine to create a concrete-like formation called a concretion. As long as the concretion remains moist, the artifacts hidden inside remain stable. But if the concretion is allowed to dry out, any artifacts inside begin to rapidly disintegrate.

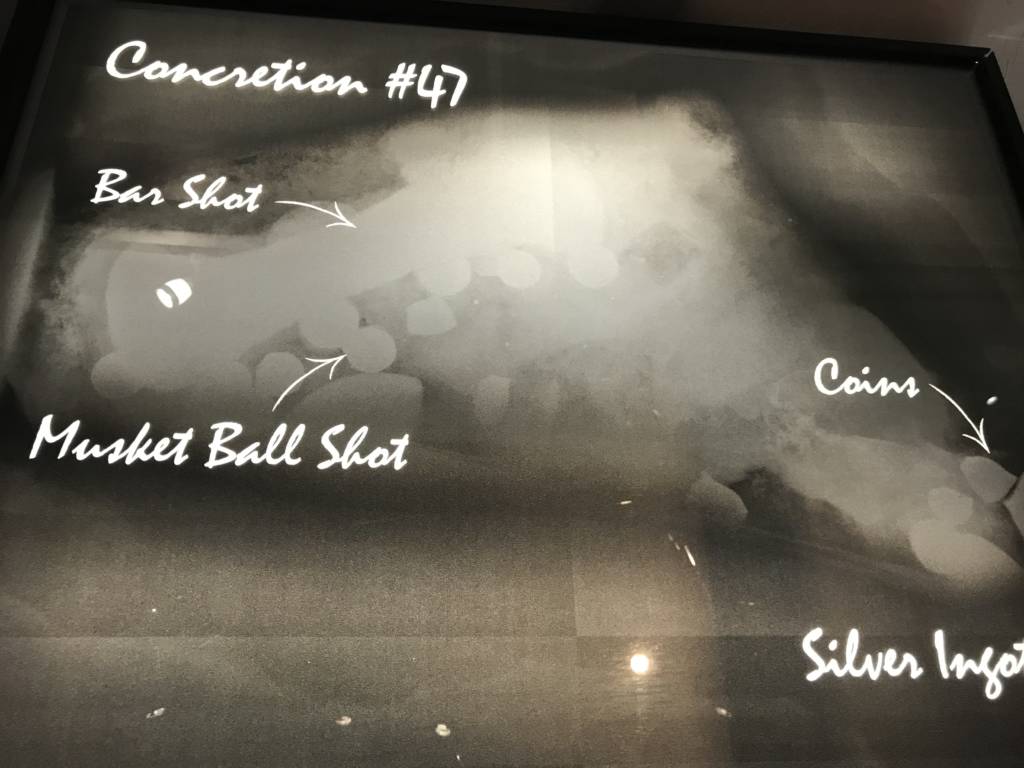

First, a diver needs to recognize a concretion when he or she sees one, and after it’s placed where it can be constantly kept wet, the process begins of discovering what artifacts might be caught inside. Two methods are used: either a concretion is x-rayed by a portable x-ray machine, which is often available on the boat as the concretion emerges from the sea, and/or a CT-scan image is taken of the concretion, which reveals a more detailed, yet more costly, view of what’s trapped inside. At the Whydah Museum, there were examples of concretions still intact being bathed by water sprays, with the x-rays taken of artifacts hidden inside, next to the concretion.

How the artifacts become separated from the concretion is a process. After being submerged in freshwater for two to four weeks, the concretion is placed in a chemical solution and low voltage electricity is applied. This process is called electrolytic reduction, and helps the salts to fall away from the artifacts, as well as any stone, iron oxide and debris that was attached. Picks, brushes and air scribes remove the remaining concretion, and the artifact is washed and coated with a sealant to protect the artifact from decay.

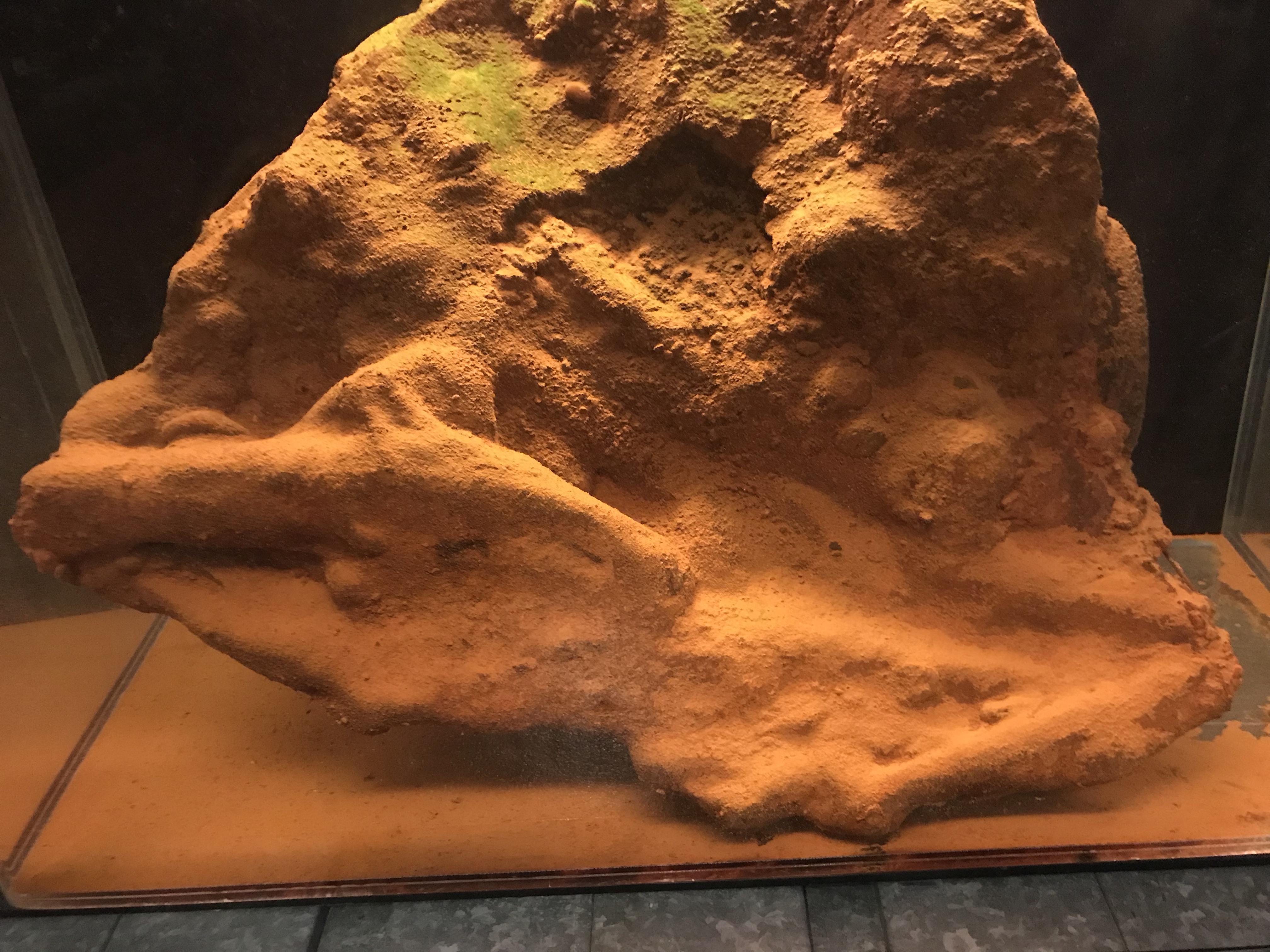

This is a large concretion that contains the bony remains of a pirate from the Whydah. Only two pirates survived the wreck of the Whydah.

In the photo above, you can actually see the pelvis bone of the pirate, still partially encased in the concretion.

Coins, pewter spoons, and loops to support the sails collected from the Whydah wreckage.

The Whydah anchor

The Whydah stove, partially exposed from a moist concretion.

The very stylish outfit divers wore while collecting concretions from the Whydah.

Can you spot the outline of a weapon in this concretion?

Add Comment